I’m grateful to have grown up alongside the mental health movement. I am happy that as I grew, the encouragement and assigned importance for having discussions about mental health grew along with me.

While by no means are mental health resources numerous or equitable enough, increasing reforms have created a social culture that is on the whole more open to discussions of well-being beyond the physical than it was in the past.

What is only beginning to be addressed at large is the anxiety surrounding the climate crisis around us, which has been termed eco-anxiety.

Unpacking eco-anxiety

Perhaps a bit surprisingly, this neologism has a concrete definition from the American Psychology Association: “the chronic fear of environmental cataclysm that comes from observing the seemingly irrevocable impact of climate change and the associated concern for one’s future and that of next generations.”

What I have always found the most prescient component of these anxieties is the inability to escape them. Walking down the street or engaging in small talk about the weather is a constant reminder (sometimes subtle, some less so) of the planet’s state. Where other anxieties can be extremely situational, existing on our planet is inescapable.

I connected with Juliette Rossignol, a Master’s student at Sciences Po and the London School of Economics, and an avid environmentalist currently researching the impacts of water corruption on the climate, to get a more concrete sense of the phenomenon.

The words that arose most often? Those of fear, sadness, anger, and helplessness: “Like many people my age, I have eco-anxiety, so sometimes I cry out of rage when I discuss these issues with people who don’t (seem to) take them seriously enough.”

I think that key components of eco-anxiety can be found in Juliette’s personal definition of the term. There is the element of it being a shared experience (especially among younger generations), but yet one that can also deeply infiltrate one’s personal headspace. There is also an accompanying desire to educate and warn others about the severity of the climate crisis, and the subsequent frustration when one feels their efforts are in vain.

Is your eco-anxiety valid?

The short answer is yes.

Eco-anxiety is in many ways the rational response to the threat posed by the climate crisis. The climate crisis forces us to come face to face with the ultimate generator of human discomfort: uncertainty.

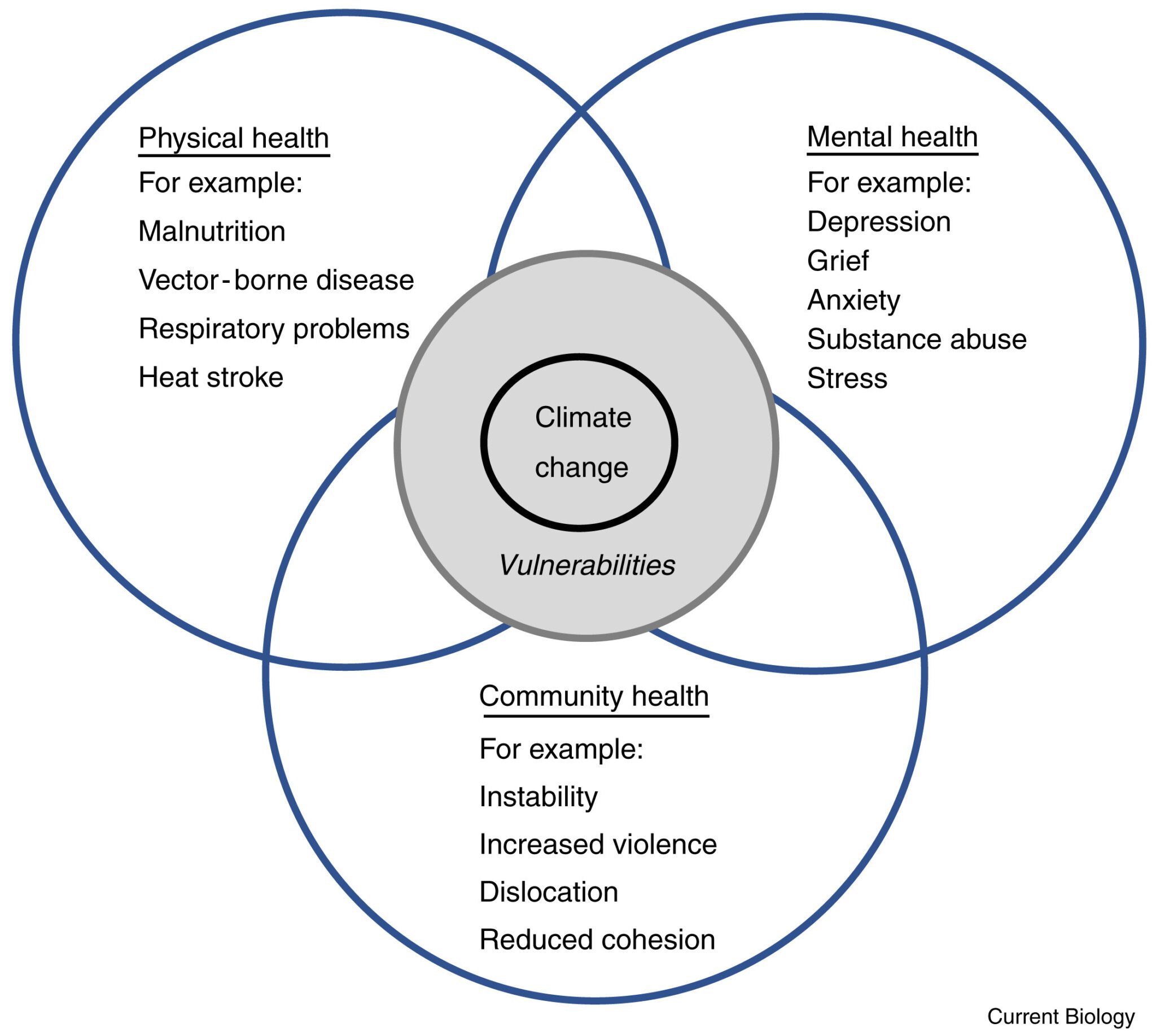

Although climate change research has historically been under the purview of the physical sciences, as physical understandings have improved, the focus has shifted to human-based studies (Susie Clayton, Psychology and Climate Change). In this domain, however, the findings are more complex and varied.

In speaking with Juliette, it is evident that some of the most prevalent manifestations of the climate crisis are water shortages. From a purely environmental standpoint, these events affect the regular functioning of water cycles. They are physically realized in the depletion of aquifers, the pollution of bodies of water, and desertification.

In communities big and small, water shortages can lead to water conflicts, public health concerns, and the disruption of ecosystems.

As the climate continues to deteriorate, these events are becoming more common. Community health effects can be further heightened by instances of water corruption – the abuse of entrusted power in the water sector for private gain. This can take the form of corruption in public procurement processes for waterworks, bribes to regulatory agencies allowing the industry to use or pollute more water than authorized, or overlooking water theft or illegal water use.

In the realm of water cycles then, eco-anxiety is the rational response to recognizing or experiencing the human vulnerabilities that present themselves when there is a shortage of water. However, as mentioned, the exact consequences on any given person are varied and unknown:

“Whether or not a young person will experience a water shortage in their lifetime depends on too many factors, from the country and region they live in, to their social class or belonging to a specific social group, because even though the biggest polluters are the richest, people with limited resources are often the most affected by climate change.” – Juliette

The potential that someone might not be forced to reckon with water shortages or other climate crises in their lifetime contributes to the division in society’s response to the climate crisis. This, coupled with common human psychological processes such as temporal discounting or allegiance to the status quo leads to the aforementioned frustration on the part of people like Juliette.

Eco-anxiety is valid and often (but not always) shared.

How to cope with your eco-anxiety

An ongoing debate in eco-conscious circles is the degree to which eco-anxiety is a productive or detrimental response in humans. While most eco-aware therapists agree that anxiety is more productive than denial, it must be carefully managed so it does not lead to helplessness and inaction.

I. Find the language and communities to address your anxieties

Finding constructive settings to discuss eco-anxieties can help keep debilitating emotions at bay. Since eco-anxiety is a newer concept, the language and community might not seem available… however, they just might take a little more looking to locate.

An ongoing art project by the name of the Bureau of Linguistical Reality hopes to provide a sense of community through language. Created by Heidi Quante and Alicia Escott, the focus is creating a new language to better explain and understand the world of manmade climate change.

Photo from the Smithsonian Magazine article on the project.

Some of my favorites include:

sostalgia (n): A form of homesickness one gets when one is still at home, but the environment has been altered and feels unfamiliar. The term is specifically referencing change caused by chronic change agents like climate change or mining.

surbrace (n): A powerful sense of conviction to do the right thing that arises after one has already let go of the outcome, because they see the situation as larger than themselves— almost as though they are already dead looking back at history.

II. Take action

Reviewing your lifestyle and assuming better daily habits when it comes to the environment can help keep your eco-anxiety productive. Aligning your practices with your ideals can help you feel less conflicted as you go about day-to-day life.

On a larger scale, the same community in which you discuss your anxieties can also be more effective in taking group action – such as organizing protests or lobbying local politicians on climate change policy.

III. Find a balance

Although you can take steps to reduce personally-caused pollution and emissions, and your community can take steps to advocate for climate matters, you cannot assume total responsibility for events like water shortages.

Putting a healthy amount of distance between your emotional well-being and the climate crisis is the difference between a breakdown and continued efforts to better the situation. Oversaturating yourself with traditional news sources sharing climate change warnings can be detrimental to maintaining the motivation to continue in your climate endeavors.

Balance out your source, by checking in with publications committed to sharing positive climate news:

- The Daily Climate’s Good News Section

- Climate Good News Instagram page

- TikTok accounts like @sambentley

Simply put, you cannot help the planet when you cannot help yourself.

Julia is a graduate of McGill University in Economics and English Literature. She’s currently working in Montreal where she loves to explore the city. She believes that open dialogue on social and environmental issues is crucial. Get in touch with her at julia[at]starduststartupfactory.org