I see Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs on my Twitter feed all the time. Or rather, I find my lips curling into a smile at badly edited images of the pyramid, its usual 5 levels blurred into 1, with scribbled writing saying that all one needs to be fulfilled is a good latte under the sunshine.

When I do this I feel guilty. I know that for many, the bottom tier of the actual hierarchy, “Physiological Needs,” is rarely (if ever) met. So many worldwide and in my own community do not have access to adequate water, shelter, or food.

Often, on the very same Twitter feed, I see calls for the world’s financial elite to solve world hunger. When probed by the World Food Programme (WFP) in October 2021, Elon Musk tweeted that if WFP could describe on a Twitter thread “exactly how $6B will solve world hunger” he would “sell Tesla stock right now and do it.”

David Beasley, the head of the WFP, quickly clarified the donation would not overhaul world hunger, but rather provide relief to those on the “brink of starvation,” which was 42 million people at the time.

Source: Twitter.

Interactions like these on social media force me to confront the ways in which I perceive food security, both globally and on a personal level. While it is abundantly clear there is a need for figures like Musk to step up, the interaction between him and WFP also points to the fact that solving world hunger is more complicated than simply having the funds.

And while I shouldn’t villainize myself for not having the resources to solve the problem myself, I need to be increasingly mindful of food insecurity in my own community, and how that situation is integrated into the global one.

Looking back on the pandemic, the United Nations estimates that 70-160 million people experienced hunger by the end of 2020) One of their top Sustainability Development Goals is their second one: Zero Hunger. They aim to end hunger and achieve food security.

In doing so, they recognize a need for promoting sustainable agriculture. They also recognize the need for increased nutrition in food available in the most undernourished areas. Food security is more than everyone having a plate of food.

A Canadian organization called Feed The Children conceptualizes food security through the Five As:

- Availability: sufficient food all the time

- Accessibility: physical and economic access to food

- Adequacy: food that is nutritious and safe, produced in environmentally sustainable ways

- Acceptability: access to culturally acceptable food, procured in ways that do not compromise one’s self-respect or human rights

- Agency: policies and processes that enable food security

When even one of these criteria is not met, an individual can experience food insecurity.

If the COVID-19 pandemic worsened food insecurity, then the Russia-Ukraine conflict is decimating it. The mass exodus of over 3 million people from Ukraine, the displacement of residents within the nation, and the destruction to land and infrastructure is contributing to rising food security concerns nationally and abroad.

A study by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations found that the Ukrainian agricultural system is reliant on a large number of small scale farms which produce over 40% of the nation’s gross agricultural product.

It is family run farms like these that are no longer able to operate due to the conflict, and they estimate that by June, supply and access to food will be a significant issue in 41.2% of cases.

Globally, Ukraine and Russia play a vital role in the food system. When coupled with Russia, the two countries account for 12% of the food calories traded worldwide (IFAD). The effects of the conflict are already being felt in Canada, despite the nation being an agricultural powerhouse in its own right.

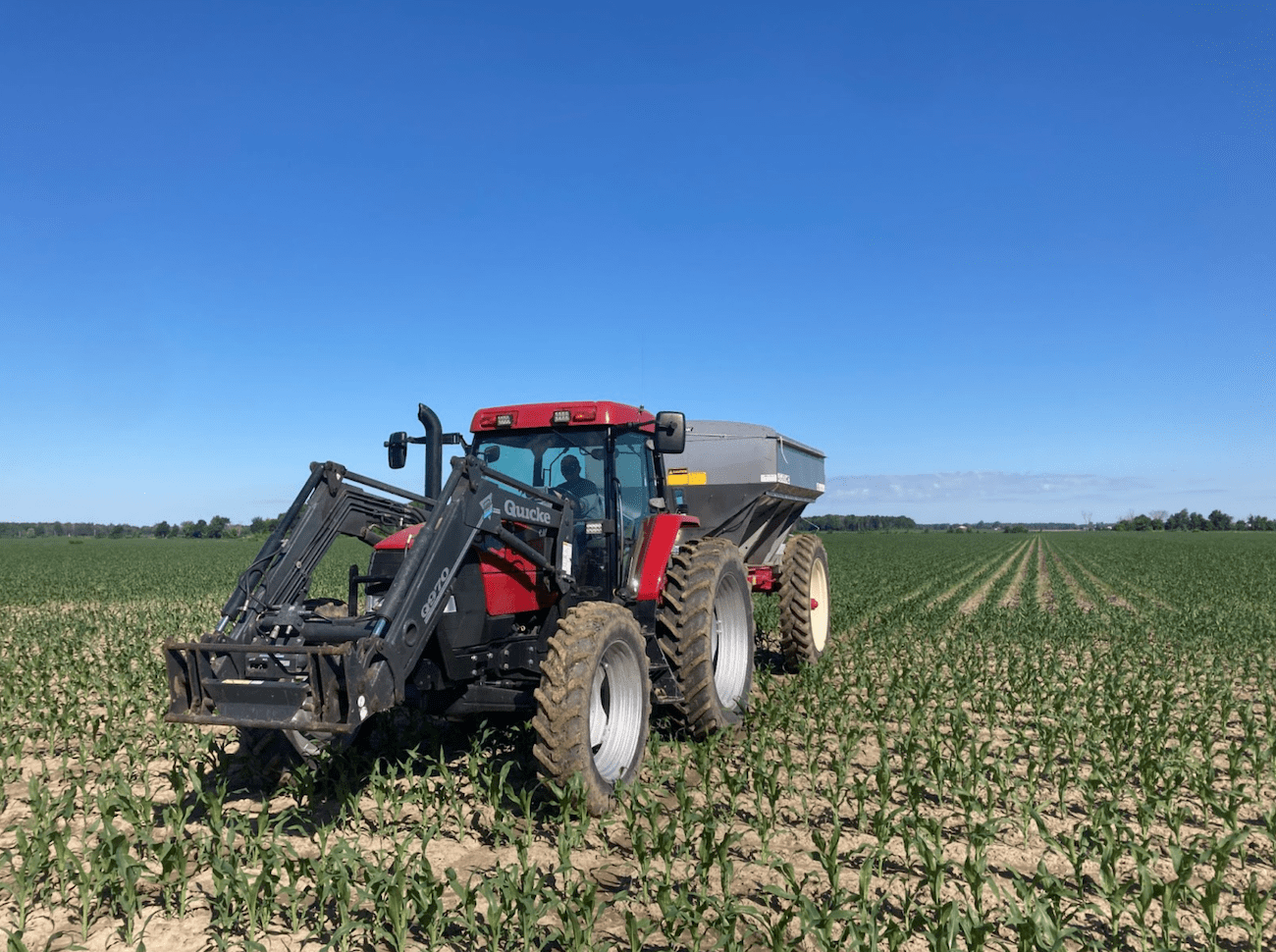

I was fortunate to speak with Paul Hermans, an agronomist who oversees farms from Ontario to the Maritimes. He listed the biggest impact on Canada so far as being the lack of fertilizer. Due to the decreased supply of a nitrogen based fertilizer from Russia, Canadian growers have had to scramble to find different sources – sometimes unsuccessfully.

Or they have simply used less fertilizer, which could diminish final yields this summer – and thus food supply.

A photo taken from Paul Herman’s Twitter. A nitrogen rate trial with an Ontario farmer.

Paul also noted that many Canadian growers place orders and pay for their fertilizer needs in December and January, and so even if they received the correct amount, they (or the retailer) have had to pay the extra costs.

The bottom line – less yield and more expensive food products for consumers. And when prices increase or people’s funds are tightened in other ways, groceries are one of the first things people cut down on, because of the need to pay mortgage or rent.

Food security actors are needed more than ever to address all the components of the issue (think: the 5 As). One of Stardust Startups’ most recent microgrant recipients is directly addressing the need for more sustainable and reliable food production processes.

The Côte d’Ivoire based project, BioAni, produces nutritious fishmeal and animal feed made from fly larvae to support the nation’s increase in fish production to help curb food insecurity.

Fishmeal represents one of the largest costs in the aquaculture process, and by creating it from fly larvae, BioAni is able to make the aquaculture financially viable. At the same time, BioAni is preserving the biodiversity of the region–limiting the number of wild fish needed to be caught, as was done before–to make the same fishmeal. In short: the production is sustainable, local, and inexpensive.

Other actors are already in place to combat the rise in grocery prices by providing direct relief to the undernourished populations. Mealcare, a non-profit with 8 chapters across Canada, has delivered close to 60 000 meals to food insecure individuals in their respective communities by partnering with other food aid organizations. The food they deliver is nutritious, safe, and would have otherwise gone to waste.

When asked about the heightened importance of such actors, Kristina Wolff, the President of the McGill University chapter of MealCare said:

“The economic effects of the pandemic, and now more global crises, have led to unprecedented demand for already-strained food assistance resources, so the work of community-based initiatives such as MealCare have been crucial for filling gaps in this system.”

As Joel Salatin puts it in his book Folks This Ain’t Normal: A Farmer’s Advice for Happier Hens, Healthier People, and a Better World : “the average person is still under the aberrant delusion that food should be somebody else’s responsibility until they are ready to eat it.” This, more than ever, should not be the case.

The Russia-Ukraine conflict has highlighted the need for increased reliability and sustainability in food production processes. Increased grocery prices have brought to the forefront the need to take care of those in the communities around us.

Ensuring we remain aware of the ever changing food security situation (abroad and close to us) is paramount. Supporting those who are set up to improve the situation is the next step – even just a little retweet of their efforts can make a world of difference.

Learn more about BioAni here.

Learn more about MealCare here.

Julia is a graduate of McGill University in Economics and English Literature. She’s currently working in Montreal where she loves to explore the city. She believes that open dialogue on social and environmental issues is crucial. Get in touch with her at julia[at]starduststartupfactory.org