T he phrase “period poverty” is an odd and unexpected combination of words.

What does period poverty actually mean? Are the struggles associated with menstruation really serious enough to earn a place alongside something as dire as poverty?

I never knew how many inequalities were produced simply by our reproductive organs when I was growing up. It was only recently that I began to learn how much period poverty affects the well-being and education of half the world’s population.

For this reason, I thought I would share with you all the main bullet points of what period poverty is and how we can work towards achieving menstrual equity.

What is period poverty?

First things first: how is period poverty defined? Simply put, period poverty is the financial inability to effectively manage menstrual health.

According to Global Citizen, menstrual hygiene management consists of three main parts:

- Being able to afford menstruation products, like pads, tampons, diva cups, or period-proof underwear.

- Accessing basic sanitary needs during menstruation, like soap, water, and safe waste disposal.

- Experiencing menstrual hygiene education, whether that be through the school system or other knowledgeable educators.

Even though period products are a basic necessity to all who require them, these products are priced and taxed as luxury items, making period products difficult to afford.

But financial insecurities lead to more health risks when menstruating individuals can’t access safe water, which is essential for cleaning, reusing, and disposing of these products. Clean water and sanitation are not just ideals for the health and well-being of menstruating bodies; according to Goal 6 of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals, access to these resources is a universal necessity.

Meanwhile, when students from low-income families cannot afford to effectively manage their periods, they have little choice but to skip class, affecting not only the quality of education but their careers.

Whether it’s from painful menstrual cramps, a lack of access to menstrual products, or the stigma-based fear of blood seeping through clothes, many students avoid school during their periods.

What does this lead to? At best, 10-20% of missed school days for students that menstruate. At worst, in regions lacking the necessary resources, education, and social encouragement, students on their periods drop out of school altogether.

So how should we move forward? One of the most useful steps to tackling period poverty is identifying and avoiding falling into the popular errors made when this issue is discussed.

3 common misconceptions

- Period poverty is only an issue in developing countries.

People tend to assume that period poverty is only prevalent in developing countries or that only a small percentage of individuals in countries like the United States and Canada struggle to buy necessary sanitary items.

However, Citron Hygiene shows that one-third of North Americans aged 25 and younger cannot afford menstrual products. And 70% of young adults in the U.S. and Canada miss school and work during their periods.

In other words, period poverty is not a distant or niche dilemma – it is shaping careers, health, and stigmas all around us.

- Period poverty only affects women.

Another big inaccuracy about period poverty is that it only affects women. However, not all women menstruate, and not only women menstruate.

Social, financial, and cultural barriers complicate menstrual health for homeless, low-income, and marginalized women, but we should remember that periods are not exclusive to cis-gender women.

- Period products aren’t that expensive.

Just for fun, I interviewed two of my male friends, Sym and Saad, to test their knowledge of period poverty and identify their misconceptions about menstrual health.

Me: How much do you think a small pack of pads costs in Canada?

Sym: $38?

Saad: $7 or $8?

The answer: between $10 and $20.

Me: What about menstrual cups?

Sym: $60. They have to last a few years.

Saad: $5.

The answer: between $20 and $40.

Me: How much did you guys learn about periods in school? Let’s test what you know through the education system – why does the body menstruate?

Saad: I learnt it in bio; I forget.

Sym: Thick lining.

Saad: Something breaks… the lining or the egg.

Me: Which one?

Saad: I don’t know – I think the egg. I don’t know.

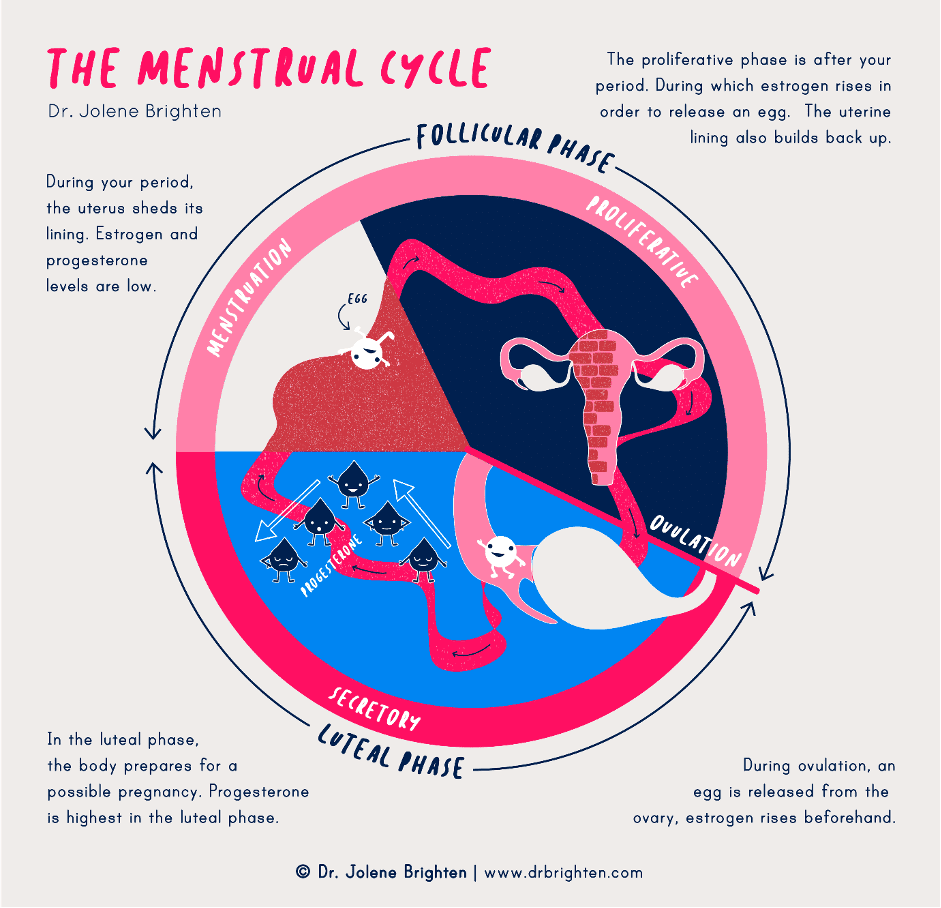

The answer: the body menstruates to release unnecessary tissue when it does not become pregnant. The lining of the uterus grows thicker to prepare for a fertilized egg, but when this egg is not fertilized, the thick lining breaks down.

Overall, even well-educated university students are uncertain about the cost of period products and the biological process of menstruation. This calls for reform in the way periods are distributed, taught, and discussed.

The entrepreneurial solution to period poverty

All of this begs the question: what can we do to help? Luckily, a handful of companies have started working towards an answer.

One way to approach the problem of period poverty is to refocus period products around empathy. Instead of talking about menstrual products as a personal purchase, some companies have started reframing the discussion of these items around compassion, community, and worldwide connections.

For example, Cora donates one month of period products and organizes better health education for those requiring it with every one month of products purchased. Cora’s donations range from India to Kenya to the U.S.

Aunt Flow adopts a similar model with the motto: “People helping people. Period.” For every ten tampons and pads they sell, one is donated to PERIOD.ORG, a nonprofit providing period products to those unable to afford them.

By recentering period products around empathy and interconnectivity, social entrepreneurs help menstruating consumers help others around the world who share their menstrual experiences but lack the same resources for managing menstrual health.

A second way social entrepreneurs combat period poverty is by using empowering language. Replacing “female hygiene” with “menstrual health” is a perfect example.

As Maria Carmen Punzi and Mirjam Werner explain, hygiene is certainly important, but this word can imply that menstruating bodies are disgusting, dirty, and undesirable. Instead, we should think of health in a way that encourages not just cleanliness but body positivity.

Periods are neither gross nor unnatural, so why should we discuss them as such?

By shifting from terms like “female hygiene” to “menstrual health,” we can start to address the social and cultural barriers to menstruating transgender and nonbinary bodies. After all, period poverty is not just a female problem. It is a universal one.

How consumers contribute

It may be easy for companies to fight period poverty, but you might be wondering – how can I help?

The short answer: invest in period products from class-conscious companies! By being mindful of which companies aim to help solve the issues entailed by period poverty, you can easily contribute to fighting period poverty just by buying your monthly stock of period products.

What if you’re someone who doesn’t go through periods? One way to help is to buy smartly from period-positive businesses like those mentioned above. Whether you’re purchasing for a family member, friend, or donation, the buy-one-donate-one business model goes a long way to helping low-income individuals get the resources they need.

Another solution: donate to one of the countless nonprofits and NGOs combatting this issue! In addition to PERIOD.ORG, plenty of organizations are set on fighting period poverty, such as Dignity Period, Days for Girls, and Help a Girl Out.

Many of these companies and nonprofits also look toward sustainable futures. For example, companies like Cora use organic cotton, moving away from period products that rely on plastic applicators and lead to plastic pollution.

We can’t achieve menstrual equity in an instant. But we can pay attention to which products promote empathy and inclusion while building connections between all those who menstruate.

The first step is simple. It only takes a tampon.

Mira is an undergraduate student at McGill University studying Political Science, Philosophy, and English Literature. She currently lives in Montréal, where she works with a variety of organizations that explore how gender, human rights, and the environment fit into the contemporary political landscape. Get in touch with her at mira[at]starduststartupfactory.org.